Hong Kong Apartment Fire: Challenges in High-Rise Building Evacuation

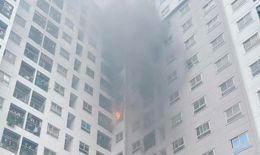

EM - When a fire erupts in high-rise buildings, the safe evacuation of thousands of people down dozens of floors becomes a race against time.

According to the most recent report from Channel NewsAsia, the death toll from the fire at the Wang Fuk Court residential complex in Hong Kong (China) has risen to 94 as of November 28, 2025. This number may continue to rise as hundreds of people remain missing.

On the morning of November 28, 2025, the Hong Kong Fire Services Department stated that the majority of victims were discovered in the Wang Cheong and Wang Tai towers, where the fire raged the most fiercely. This stands as the deadliest fire in Hong Kong since 1948, when an explosion and subsequent fire claimed 135 lives.

Although more than 900 people have been evacuated from Wang Fuk Court, it remains unclear how many residents are still trapped inside.

This catastrophic fire—believed to have spread from one building to another via materials used in renovation work and fanned by strong winds—has starkly exposed the difficulties of evacuating high-rise buildings in emergencies.

The buildings are surrounded by bamboo scaffolding and construction netting. (Ảnh: Reuters)

A Race Against Time: When Risks Reach Their Peak

Emergency evacuations in high-rise buildings are rare occurrences, but when they do happen, the consequences are often devastating. The risk is highest in buildings that are densely populated at specific times, such as residential complexes at night or office buildings during the day.

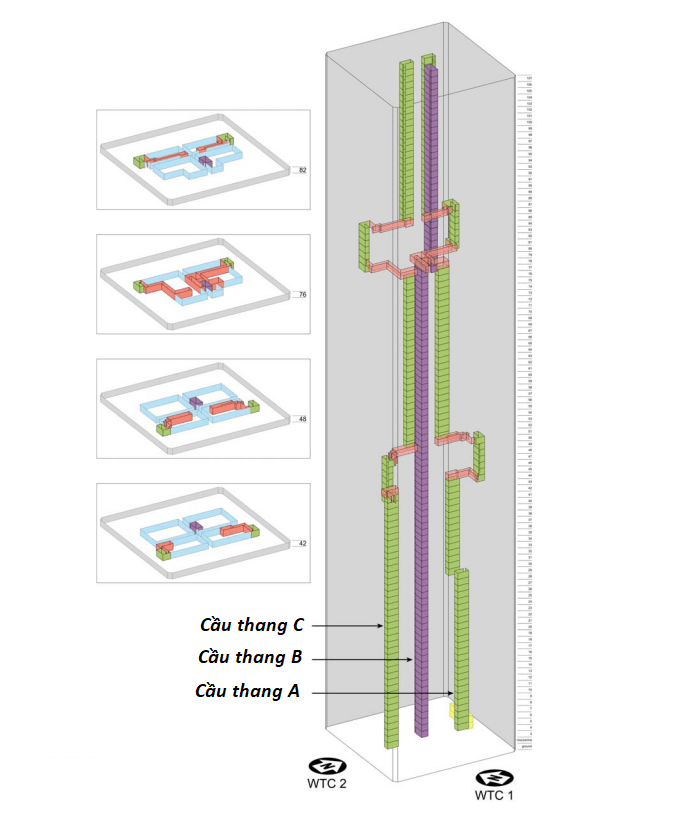

Catastrophic fires in modern history, such as the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center (USA) which claimed nearly 3,000 lives, or the Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 which killed 72 people, are stark examples of the tragic consequences of failed evacuation efforts.

Recurring Scenarios: Once a fire breaks out, bringing thousands of people safely down dozens of stories becomes a race against time.

But what exactly makes evacuating a high-rise building so difficult? The challenge is not merely about "getting everyone out," but also depends on human behavior under life-threatening pressure and the specific characteristics of each structure.

An elderly man is distraught outside a burning apartment complex, knowing his wife is still trapped inside (Ảnh: Reuters).

The Challenge of Distance and Physical Limitations

The biggest barrier is simply the distance from the upper floors to the ground. Stairwells are the only reliable escape route in most fires, but descending them during actual evacuations is much slower than most people imagine.

Under controlled conditions or during drills, people descend at a speed of approximately 0.4 to 0.7 meters per second. However, in real-life emergency situations, particularly in high-rise fires, this speed can drop significantly.

During the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, the recorded descent speed of survivors was often less than 0.3 m/s. This speed decreases further in skyscrapers, where the distance that must be covered via stairs is extremely long.

Diagram simulating the stairwell shaft at the World Trade Center

Prolonged walking leads to fatigue, significantly reducing descent speed. Post-incident surveys indicate that the vast majority of high-rise evacuees stop to rest at least once.

In a 2010 high-rise fire in Shanghai, nearly 50% of elderly survivors stated they were unable to maintain their pace throughout the evacuation. Notably, when crowds from multiple floors merge into a single stairwell, congestion is very likely to occur.

Slower movers include older adults, individuals with physical or mobility impairments, and groups evacuating together. This reduces the overall movement speed compared to what is typically assumed for able-bodied individuals, potentially creating bottlenecks.

One of the emergency stairwells in WTC Tower 1, photographed during the evacuation on September 11, 2001.

Slow movers are particularly common in residential buildings, where a diverse resident population implies that movement speeds vary significantly.

Visibility also has a major impact on evacuation speed. Empirical studies show that when smoke reduces visibility during actual incidents, movement can become even slower as people tend to hesitate, misstep, or subconsciously adjust their pace.

Psychology and Behavior in Emergencies

According to experts, human reaction in emergencies is another major cause of delays in high-rise evacuations. People rarely act immediately when the fire alarm sounds. They hesitate, seek confirmation, assess the situation, gather belongings, or coordinate with family members.

These initial minutes are almost always the most "costly" in a high-rise evacuation.

Studies on the evacuation during the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center reveal that the more cues people perceived—smoke, vibrations, noise—the more they sought additional information before moving.

This search for further information compounds the delay. People talk to colleagues, look out windows, call family members, or wait for announcements. Ambiguous cues slow them down even further.

Residents burst into tears at the sight of the fire. Many people were evacuated during the fire at the Wang Fuk Court residential complex in Hong Kong on November 27, 2025.

In apartment buildings, families, neighbors, and groups of friends often attempt to evacuate together. Such groups occupy more space or tend to cluster, reducing the overall flow of movement within the stairwells.

Research indicates that when a group moves in a "snake" formation—moving single file—it typically results in the fastest evacuation speeds. This formation occupies less space and allows others to overtake easily, preventing localized congestion.

Rethinking Escape Routes: Stairwells Are Not Enough

As high-rise buildings grow taller and populations age, the old assumption that "everyone can take the stairs" simply no longer holds true. Full building evacuation can take an excessive amount of time, and for many residents (the elderly, those with limited mobility, and families evacuating together), descending long flights of stairs is sometimes impossible.

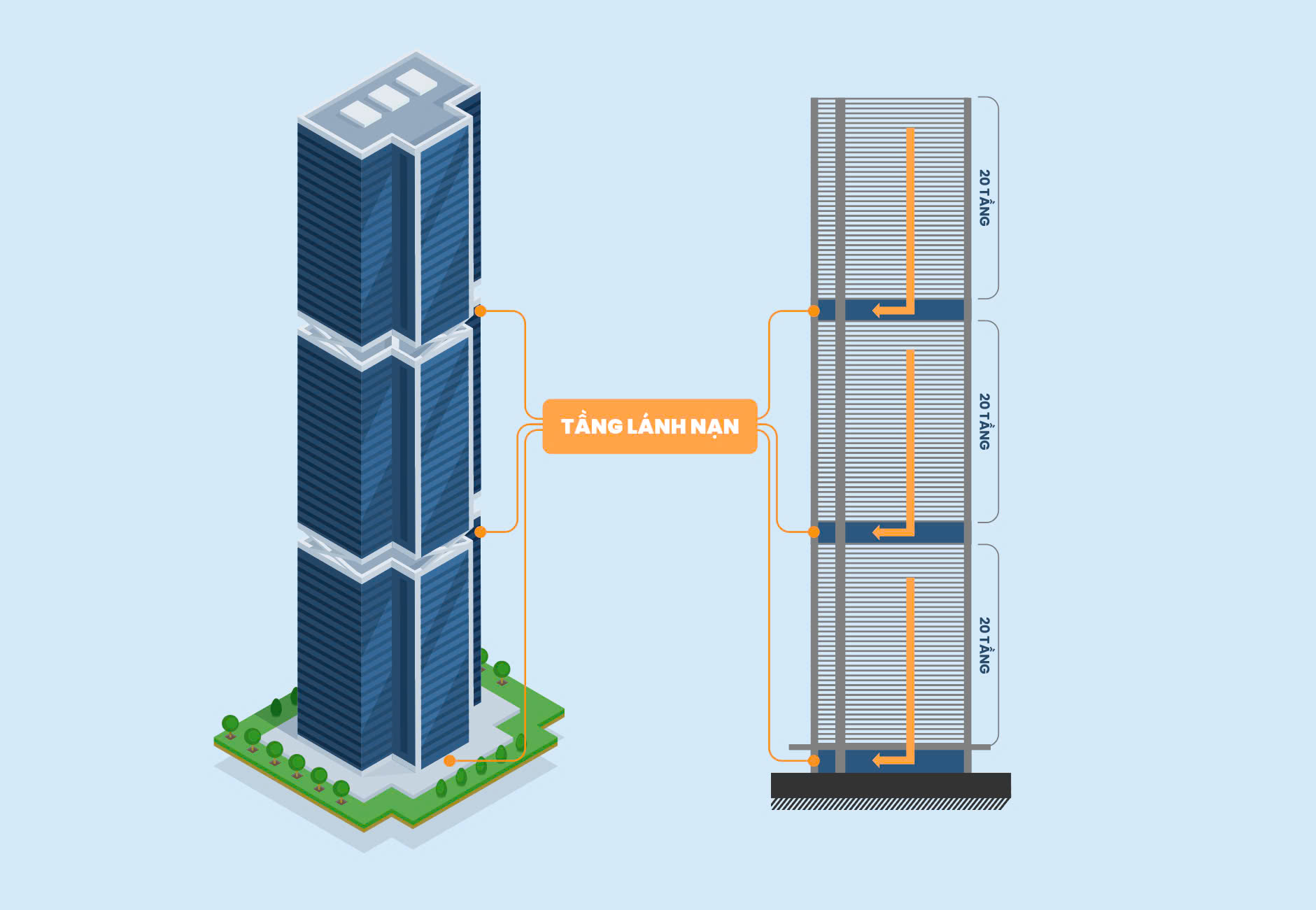

This is why many countries have adopted the concept of refuge floors: floors protected from fire and smoke, incorporated into high-rise and supertall buildings as safe assembly points. These refuge floors can help alleviate bottlenecks and prevent long queues of people waiting to be evacuated.

Thanks to a special zone known as the refuge floor, over 100 people in the 33-story Samwhan Art-Nouveau building in South Korea escaped a massive fire lasting nearly 16 hours in October 2020 without sustaining serious injuries.

Refuge floors provide people with a safe place to rest, transfer to a stairwell with better visibility, or wait for firefighters. Essentially, refuge floors make vertical movement more manageable in buildings where continuous descent is impractical.

According to QCVN 06:2022/BXD, refuge floors must be spaced no more than 20 floors apart, with the first refuge floor located no higher than the 21st floor. The area designated for the refuge zone must be separated from other areas by fire barriers with a fire resistance rating of not less than REI 150.

Complementing the refuge floors are evacuation elevators—elevators designed to operate during a fire, featuring pressurized shafts, protected lobbies, and a backup power supply. The most effective evacuations utilize a combination of both stairs and elevators, with the strategy tailored to the building's height, density, and occupant characteristics.

Standards for evacuation elevators are referenced in CEN/TS 81-76, ISO/TS 18870, ASME A17.1, and Draft CEN prEN 81-76. In Vietnam, there are currently no specific technical regulations or standards for evacuation elevators.

Recently, the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) officially issued a new design standard for evacuation elevators. The full title of the standard is "Standard EN 81-76:2025 – Safety rules for the construction and installation of lifts – Particular applications for passenger and goods passenger lifts – Part 76: Evacuation of persons with disabilities using lifts."

In Vietnam, "firefighting elevators" are designed to simultaneously meet the needs of the fire brigade and support evacuation; however, the use of firefighting elevators for evacuation purposes has not yet been described or regulated in detail.

In Vietnam, there are currently no specific technical regulations or standards for evacuation elevators. Current regulations, such as TCVN 6396-72:2010, only address the use of firefighting elevators for evacuating people from fires to a rather limited extent.

The lesson is clear: High-rise evacuation cannot rely solely on a single means. Stairs, refuge floors, and dedicated evacuation elevators must be seamlessly integrated to ensure safety in high-rise and supertall buildings.

Content authored by: Phuong Trang

![[Photos] Impressions of Vietnam Elevator Expo 2025 [Photos] Impressions of Vietnam Elevator Expo 2025](https://media.tapchithangmay.vn/share/web/image/2026/1/mobi6703639038935945497270_350x210.webp)