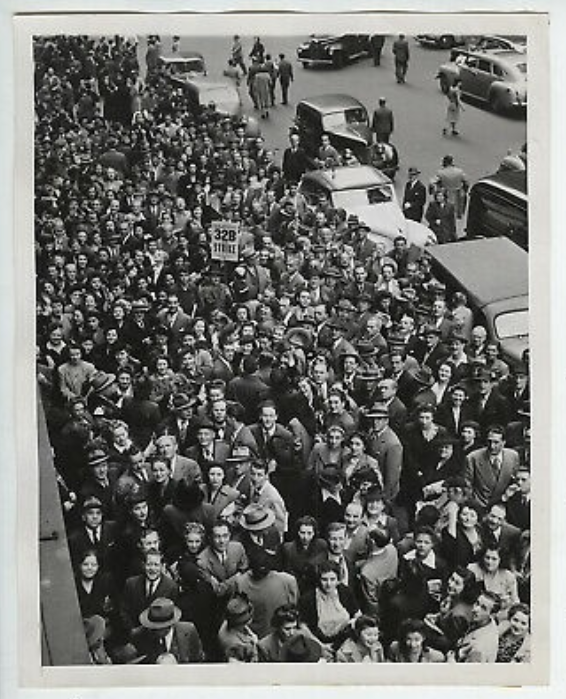

Elevator operator strikes had a particularly significant impact compared to those in other sectors, such as buses, taxis, or subways. These events once brought New York City in the U.S. to a standstill, resulting in losses totalling hundreds of millions in tax revenue.

Elevator Operators’ Strikes

Between the 1920s and 1960s, elevator operators across the United States frequently went on strike, demanding higher wages, shorter hours, and better working conditions. One of the earliest notable strikes took place in April 1920, when 17,000 operators walked off the job in New York City.

Although this strike lasted less than a week, around 5,000 operators successfully negotiated new contracts with improved benefits.

In April 1934, New York elevator workers established Union 32B. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, within just five years of its founding—by 1939—more than 12 elevator worker strikes had occurred nationwide, involving over 6,700 workers.

Female elevator operators protested at the Empire State Building, New York, in 1945. The strike forced thousands of employees working in skyscrapers to climb the stairs to reach their offices. (Source: Picclick)

One of Union 32B’s biggest victories came in 1945 when a multi-day strike led to a 10-year peace agreement and an anti-discrimination policy.

During the week-long strike, elevators across the city remained “frozen” and were left entirely unused. Despite having watched operators manage the controls, people refused to approach them. The idea of an ordinary person operating an elevator on their own had, at that time, become a genuine source of fear for the public.

According to Popular Science, elevator operator strikes had a greater impact than strikes in other transportation sectors, as they had the potential to paralyse an entire city.

Unlike bus, taxi, or subway strikes, which allowed people to find alternative ways of getting around, very few were willing or able to climb more than 5 or 6 floors to get to work. The business and commercial activities of New York City were nearly brought to a standstill when elevator operators went on strike.

The image of the crowd from the 32B Union on strike and marching in protest in 1945. (Source: Picclick)

With approximately 15,000 elevator operators on strike across New York City buildings, the entire city came to a halt, resulting in a loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue. Up to 1.5 million residents are estimated to have been unable to go to work due to the strike.

The popularisation of automatic elevators

Although the first automatic elevator technology appeared in 1887, public trust in automation was initially low, preventing widespread adoption. To address this issue, a promotional campaign was initiated to assure the public that elevators could function safely without human operators.

Advertisements featured images of children and the elderly riding elevators and operating them independently. These elevators were also equipped with voice prompts to guide passengers in selecting their desired floors by pressing the corresponding buttons.

The first fully automatic elevator was installed by the Otis Elevator Company in 1950 at the Atlantic Refining Building in Dallas, Texas. This marked the beginning of the automatic elevator industry and the end of the “elevator operator” profession.

As public acceptance of automatic elevators grew, people became more accustomed to using them without operators. Consequently, labour strikes by elevator operator unions lost much of their previous impact.

An elevator company employee supported the use of automatic elevators by stating that they (automatic elevators) didn’t go on strike, get sick, or step outside for a smoke, as reported in Popular Science in July 1959.

Image of skyscrapers in New York City in 1952. (Source: History 101)

Beyond eliminating the negative impacts of elevator operator strikes, a study was conducted on 14 buildings: half with automated systems and half with elevator operators. The results showed that automated elevators were faster and had a 10% higher capacity since they did not require operators.

The two main responsibilities of elevator operators—opening and closing the doors and controlling the speed and direction of the elevator—were officially automated. Manual levers were replaced with control panels.

In the following years, the introduction of emergency phones and stop buttons further accelerated the process of making elevators more accessible to the public. All of these changes contributed to increased safety measures for automated elevators.

Elevator Operator Jobs Gradually Disappeared

With the introduction of safety features, users who were initially hesitant about automated elevators eventually gained more trust. They could be reassured knowing that help could be requested with a phone call or by pressing an emergency button and that passengers could stop the elevator at any time with the push of a button. All of this contributed to a greater sense of safety.

As these features were rolled out, additional ones were added—security cameras and other control devices. From just 12.6% of elevator orders being for automated systems in 1950, by 1959, this number skyrocketed to over 90%.

Elevator Operator at William Taylor Department Store in 1961 (Source: CMP Cleveland Memory)

In a 1966 hearing before the U.S. Joint Economic Committee (JEC), after a union of elevator operators in Illinois, Chicago successfully negotiated a wage increase to $2.50 per hour. Building owners quickly spent $30,000 per elevator to transition from manual operation to an automated system.

By the 1970s, most elevators operated without an operator, leading to thousands of job losses.

According to research by Harvard economist James Bessen, only one of the 270 detailed occupations listed in the 1950 U.S. Census was eliminated due to automation. That job was an elevator operator.

Today, discussions often centre around a key question: What roles can machines replace? The potential of automation technology continues to advance at an unprecedented rate, from machine learning and robotics to breakthroughs in AI, IoT, and big data, driving the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Just as the elevator operator job was once common, the development and implementation of technology to replace human labour, either partially or completely, is an inevitable trend. What’s crucial is that we—as workers—need to recognize this trend clearly and prepare ourselves for the future.