A construction project may be divided into multiple phases, but with each new building that rises, a new brand of equipment—and an elevator manufacturer—seems to make its debut.

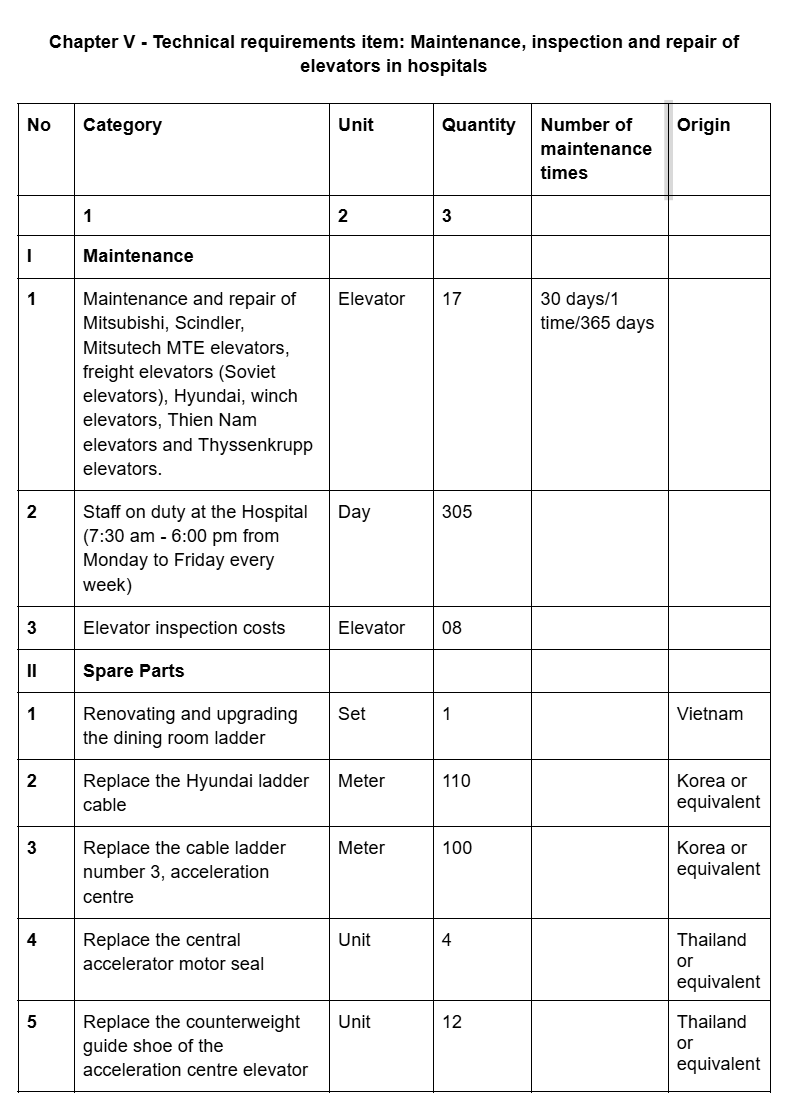

While reviewing the “Chapter V – Technical Requirements” of a project in Hanoi, we were struck by the sheer diversity of its elevator specifications: nearly 20 elevators installed across different buildings, representing six to seven brands, spanning everything from imported models to domestic ones. Each building appears to have its own “personality” reflected in the choice of elevator brand, resulting in a “collection” so varied it is almost unbelievable—yet it exists within the same development complex.

The most significant differences among elevator brands lie in their proprietary technologies. Each manufacturer employs control software, electrical and electronic systems, components, and technical protocols. Meanwhile, under legal regulations, maintenance contracts cannot be split into smaller packages, and to reduce costs and streamline processes, investors often prefer to appoint a single contractor to maintain the entire system, regardless of the number or variety of elevator brands involved.

This raises a series of critical questions: Can the chosen contractor truly possess the technical expertise to access, analyse, and service multiple systems from different manufacturers? Do these brands officially authorise them to supply genuine, standardised, compatible parts for repairs and replacements when needed?

If not, what assurances remain that such repairs or replacements will not compromise the equipment’s safety and reliability?

In reality, many investors show little interest in continuing maintenance contracts with major elevator brands once a project is handed over due to higher costs and minimal “kickbacks.” Instead, they turn to lower-cost maintenance companies that offer more generous commissions, often at the expense of technical competence.

Equipment degradation becomes inevitable when a contractor takes on too many elevator brands without specialised expertise or the capability to source genuine, high-quality parts. Without proper replacement using standardised components, systems quickly fall into disrepair.

Some incidents stem from minor faults, but technicians may resort to makeshift solutions due to inadequate skills: installing incompatible parts, bypassing control circuits, or turning off safety functions entirely. While these improvisations may keep the elevator running in the short term, they pose serious long-term safety hazards.

When internal staff enable violations

The deterioration of elevator systems is not always solely due to contractors’ limited capacity. More alarmingly, in many cases, internal elevator management teams actively collude in violations, profiting from using substandard components or even declaring parts as “faulty” when they are still functional to replace them for personal gain.

These “under-the-table” arrangements between building management and maintenance contractors can result in elevators in good working condition being falsely reported as broken, dismantled, and replaced with low-quality, uncertified parts. The outcome is a once-standard, fully compliant elevator system becoming patchy, unreliable, and unsafe.

A notable example is the inflated elevator pricing scandal at the Mieu Noi apartment complex, prosecuted at the end of 2024. In 2018, instead of installing a VND 1 billion elevator as per the signed contract, the building’s management board conspired with Dai Tien Elevator Company to import parts from Thailand and South Korea, adding locally fabricated components for assembly.

The total cost of the assembled elevator was only VND 800 million, leaving a VND 200 million difference—funds that were subsequently siphoned off.

The investigative agency has issued procedural decisions against Phạm Phương, former head of the Miếu Nổi apartment complex management board.

The violations did not stop at the 2018 incident. In 2019, the management board signed another contract with Đại Tiến Elevator Company to install three elevators. Only two were installed, yet full payment was made for all three, inflating the project cost by VND 600 million.

This blatant lack of transparency and profiteering not only compromised the quality of the project but also directly endangered the safety of residents.

The challenge of cost-effective and transparent elevator management

Elevator maintenance and repair are not merely technical matters but complex issues intertwined with governance, ethics, and transparency. To address these long-standing problems, a fundamental shift in both mindset and action is required from all stakeholders.

1. The most effective way to ensure technical quality across an elevator system is to assign maintenance tasks to each manufacturer. This means that each elevator brand—or an authorised service provider—would be solely responsible for the upkeep of its equipment.

However, this approach comes with its managerial challenges. Coordinating and supervising six to seven separate maintenance contractors becomes a logistical puzzle for a project with six or seven different elevator brands. Investors would face issues of inconsistent processes, conflicting maintenance schedules, and unclear accountability, all of which demand a highly disciplined management system.

The issue becomes more complicated even for maintenance contracts funded by the state budget. Each contractor offers different service pricing, making it difficult to justify expenditures during inspections or audits. More critically, dividing maintenance services among multiple contractors can be deemed a violation of regulations against “deliberately splitting contract values,” which may lead to unnecessary legal breaches.

2. A viable approach to optimising management efficiency and costs is to appoint a single general contractor with sufficient technical expertise and capacity to maintain the entire elevator system.

To ensure the contractor’s capability, the project owner should require official authorisation from each respective elevator manufacturer confirming the long-term provision of genuine spare parts and equipment. This is a fundamental condition to ensure maintenance quality and system synchronisation, and prevent risks arising from using uncertified or non-genuine components.

Only with such transparent authorisation can the project owner have complete confidence in the quality of service and the safety of the entire elevator system.

3. An independent inspection mechanism is essential to guarantee transparent elevator management and operation.

Any proposal to replace key components—especially critical ones such as control boards, motors, or safety devices—should be objectively evaluated by an independent inspection body, free from any influence by the maintenance contractor.

Publishing all relevant records and making the replacement process transparent will significantly reduce malpractice while enhancing accountability across all parties involved. This is a decisive step toward safeguarding the interests of project owners, ensuring construction quality, and most importantly, guaranteeing the absolute safety of users.

An elevator is not just another piece of equipment—it is the lifeline of every high-rise building. Any oversight in maintenance or repair can lead to serious incidents. While cost savings are essential in any project, cutting corners the wrong way transforms savings into massive waste and exposes the building to unpredictable dangers.